I set out to assemble a varied stack of books for the summer - across genres, geographies, moods. It didn’t quite work. The selection (predictably) leans toward female authors, a certain existential register, and a recurring preoccupation with relationships, consciousness, and fragility. It’s not curated along any ideological lines, but it’s hardly random either. Some of the books have been sitting on my shelf for too long; others are new obsessions. A few I’ve only skimmed, some I’ve started without finishing - yet.

Most of them were chosen with a kind of embodied reading in mind: books I can carry, read slowly, put down and return to in rhythm with the journey. I’m heading first to Portugal’s southern coast, then driving north toward Lisbon, and the books are coming - not as escape, but as interruption, friction, and, at times, companionship.

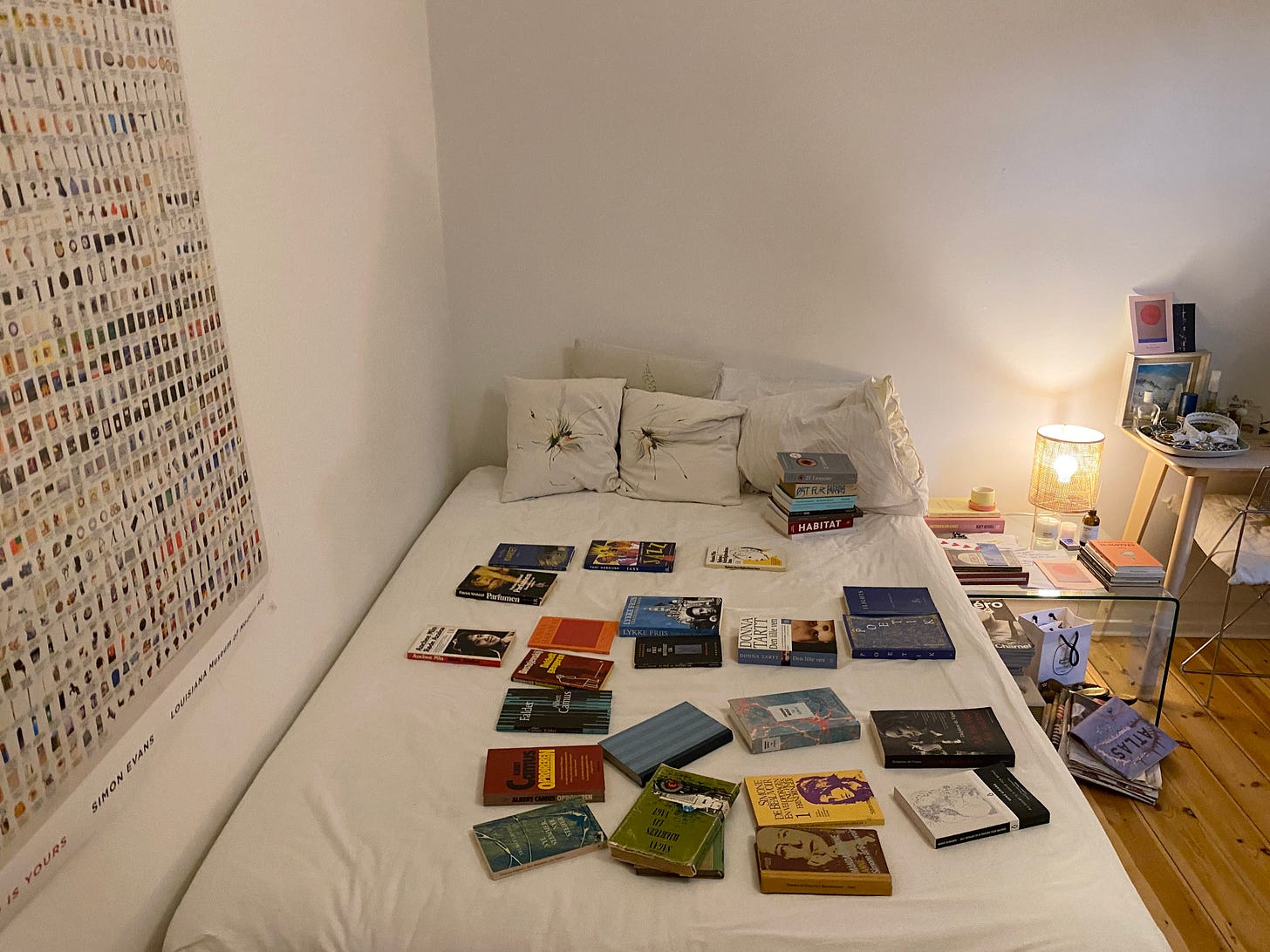

Here’s what I’ve packed.

Tove Ditlevsen – Dependency

I begin with Ditlevsen, because she’s the only writer on this list who feels viscerally necessary to me. Dependency is the final volume of her Copenhagen Trilogy and arguably the most devastating. The Danish title, Gift, translates both as "poison" and "married", a dark linguistic pun that encapsulates the entwinement of romantic submission and addiction. Ditlevsen always writes with the precision of someone who knows that telling the truth is both a compulsion and a curse. Her descriptions of drug use, of motherhood, and of the unbearable weight of expectation - both internal and external - are never indulgent, but deeply interior.

Jean Rhys – Quartet

I’ve long been drawn to Jean Rhys without fully reading her, and Quartet seems like the right place to begin. It’s one of her early novels, based in part on her own entanglements in interwar Paris, and offers a portrait of a woman suspended between abandonment and coercion. What I find so compelling about Rhys - at least from what I’ve read around her work - is her almost forensic sensitivity to the subtle violences of gender and class, especially as they unfold within romantic and economic dependency.

Quartet tells the story of Marya, who is cast aside by her lover and gradually absorbed into a parasitic relationship with a married couple who promise protection but offer only control. I’ll read this in Lisbon where old buildings lean toward one another and streets fold in on themselves like secrets.

Hannah Arendt – Existence and Religion (Eksistens og religion)

This is perhaps the most intellectually ambitious book in my suitcase - and also the one I feel most tentative about. Eksistens og religion is a Danish collection of Arendt’s lesser-known essays and lecture fragments. I’m drawn to the title, of course: existence and religion, those twin chasms. Arendt’s thinking has always appealed to me because it insists on the messiness of the world - not in order to celebrate it, but to stay with it. Her work resists abstraction without ever becoming merely reactive. I expect to read this slowly, probably not all at once, and likely in strange, disjointed moments - before sleep, after swimming, when the mind is loosened.

Josefine Klougart – After Nature

After Nature is an extended essay - part literary criticism, part philosophical reflection, part personal manifesto - on what art can (and cannot) do in a time of crisis. It was written in dialogue with specific works from the Glyptotek’s collection in Copenhagen, but the text stands on its own as a sweeping inquiry into the aesthetic experience and its political implications. Klougart asks questions that feel especially urgent now: What kind of responsibility can we reasonably place on literature? Is it enough for art to be beautiful, or must it also be useful, ethical, transformative? And what does transformation even mean?

Gabriel García Márquez – Of Love and Other Demons

Of Love and Other Demons is one of Márquez’ shorter novels, but from what I gather, it carries his signature mix of myth, sensuality, and political grief. The story is set in colonial Colombia and centres around a twelve-year-old girl believed to be possessed. His prose has a musicality to it, a weight and warmth that I think will resonate with the Portuguese landscape - its decaying grandeur, its melancholic light. I want to read this novel slowly, allowing it to pull me under like a warm tide. Not to escape reality, but to see how many kinds of reality might exist at once.

Clarice Lispector – To Write and to Live

To Write and to Live is a collection of fragments, crônicas, and short prose texts about the act of writing as a mode of survival and astonishment. I expect it to be a slow, porous read - something to dip into in the morning, with coffee and light coming in slant. There’s a strange paradox in Lispector’s work (as described by those who love her): it’s abstract and metaphysical, yet somehow bodily, intimate, and I hope to experience that paradox firsthand.

Jaron Lanier – Ten Arguments for Deleting Your Social Media Accounts Right Now

This is the only book on my list that reads like a manifesto - and deliberately so. I’m bringing it not just because I expect to be convinced, but because I want to understand more clearly how digital life shapes us, even in absence. Lanier is a technologist who once helped build the world he now critiques, and his arguments are equal parts moral, political, and existential. This isn’t a book I’d typically bring on vacation, but there’s something appealing about reading it while deliberately disconnecting.

Simone de Beauvoir – Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter

De Beauvoir’s early memoir feels like a foundational text for anyone trying to think seriously about how a woman becomes herself under patriarchy. I haven’t yet read it in full, but from the excerpts I’ve encountered, it’s clear that she approaches her own formation not as a private journey, but as a collective one - something I’ve greatly appreciated in other works such as Annie Ernaux’s The Years.

She writes about her childhood, her intellectual development, and her early defiance of bourgeois expectations with a kind of analytical detachment that resists sentimentality. And yet the emotional undercurrents are strong - particularly in her relationships to her family, religion, and writing. I’m interested in how she narrates her passage into philosophy, not as a liberation from femininity, but as a confrontation with its constructedness.

Albert Camus – The Fall

The Fall is a monologue, an accusation, a confession - all spoken by one man in an Amsterdam bar. Camus’s narrator, Clamence, tells the story of his fall from grace: how he went from being a “good man” to someone who lives in constant, bitter self-awareness. What fascinates me is the way the novel dismantles the idea of virtue - not by opposing it, but by hollowing it out. Everything becomes a performance, and no act of goodness is free from the desire to be seen as good. I think it will be the book I read when I need to come down from all the emotional texture of the others - when I want something sharp and clean, almost surgical. Camus doesn't moralise, but he doesn’t let you look away either.

Françoise Sagan – A Certain Smile

I picked this book partly because I wanted something deceptively light. Sagan’s novels are known for their clarity, their surface elegance, but also for the emotional undertow that runs just beneath. A Certain Smile follows a young woman, Dominique, who begins an affair with an older man - her lover’s uncle, no less - and who narrates the entire thing with unnerving coolness.

Sagan’s characters are often described as bored or emotionally listless, but I think that’s a misreading. Beneath the cynicism is a kind of wounded openness: the awareness that feeling too much is dangerous, so one must learn to glide.

Ia Genberg – The Details

This novel entered my list through word-of-mouth whispers rather than algorithmic recommendation. Genberg’s book is about memory - how it moves, how it attaches itself to others, how it remakes us through the act of remembering them. The narrator is sick with fever, and in that altered state, she begins to conjure up four figures from her past: people she loved, or was entangled with, or couldn’t quite become. I’m intrigued by how the book seems to suggest that the self is not a solid centre but a pattern of attachments, reencountered through time. What makes me most curious is the form: a loose constellation of vignettes rather than a linear narrative.

Delphine de Vigan – Nothing Holds Back the Night

De Vigan’s Nothing Holds Back the Night is a kind of narrative inquiry into her mother’s mental illness and suicide - a book that seems to hover between novel, memoir, and investigative report. What draws me to it is the structural and ethical complexity. How do we write about the people we love without turning them into symbols, characters, or evidence? How do we tell stories that involve pain without aestheticising it? I’m curious to see how this book holds these questions.

Anaïs Nin – A Spy in the House of Love

Nin’s A Spy in the House of Love is one of her so-called “Cities of the Interior” novels - a series that explore the lives of women through dream, desire, and fragmentation. The protagonist, Sabina, lives several lives at once, each version of herself slightly out of sync with the others. I think what I’m looking for in this book is an account of feminine subjectivity that’s unstable and fluid, not tragic or psychologised. Nin doesn’t write “about” women - she writes through the atmospheric distortions that come with being one. I imagine reading this at night, maybe slightly disoriented by travel and heat, when it feels most natural to slip into someone else’s consciousness.

Theis Ørntoft - Habitat (Hasn’t been translated into English yet)

Set on the remote island of Møn, the story follows a man retreating from the world, trying to find peace through writing and isolation. But peace remains elusive: as nature invades the house and silence turns uneasy, the boundaries between his mind and reality begin to blur. Habitat promises to be a dense, atmospheric read, perfect for those moments when the world feels both too loud and too empty. I’m eager to see how it holds up as both a psychological study and a reflection on what it means to be alone as a man in today’s world.

Over the summer, I’ll share my thoughts on each as I go, letting the reading unfold alongside the travel and the quiet moments in between.

If you’re curious to follow along, stay tuned.

Thanks for being here.

Bye for now <3333